As we started to talk about urban practices, we became curious to find out more about the people who bring these concepts to life. What does it take to become an urban practitioner, and how do they measure the impact of their work? Is there a typical background for those in this field, and how do they choose relevant topics? We invited Tinatin Gurgenidze and Vivian Doumpa, urban practitioners with unique perspectives on the field, to share their insights into their work in architecture, urban planning, education, and placemaking.

Tinatin Gurgenidze lives and works between Berlin and Tbilisi. She has studied architecture and urban design in Tbilisi and Barcelona, is the author of several publications and has curated exhibitions and projects in recent years. She is also a co-founder of the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial.

Vivian Doumpa is an Athens-based urban planner and geographer, with a specialisation in creative and inclusive placemaking. She has international experience in placemaking and citizens’ inclusion in urban planning, especially on matters of public space and neighbourhood revitalisation. She is a co-founder of the local office of STIPO in Greece, and a board member of Placemaking Europe.

Katya: I was always struggling to find the correct words for people who work in the field of urban practices. Could you please briefly introduce yourselves and help me find the most fitting words to define your work?

Tinatin: I’m Tinatin. I’m a trained architect, but at the moment I’m mostly involved in organizing large events. I’m also an urban researcher, a cultural worker and a curator with a focus on cities and architecture. Even though I live in Berlin, my work is strongly connected with Georgia.

Vivian: I’m Vivian. There’s always an identity issue here. My mum keeps asking me, what did you say you do in your life? I studied engineering, which means that I have learned to operate on completely different levels when it has to do with space. So this has definitely helped me develop my identity.

I’d also like to say that I’m a placemaker. Here I want to go away from a trendy kind of approach to what placemaking is: not how we can create better places but what it means to be able to be part of a place and see what it has to offer. What I love to do is to be in places and among people, facilitate, and help with processes; a big part of my work has to do with culture, creativity and education. So I’m definitely not a typical urban planner, especially in the context of Greece. Currently, I coordinate the local office of STIPO, the international organisation around human-centred cities, based in the Netherlands. Parallel to that, I’m a board member of Placemaking Europe, the European network that connects practitioners, academics, community leaders, market players and policymakers across the field of placemaking.

Katya: What got you curious about the cities? I wonder if there was any inspiration or combination of things that led you to where you are.

Tinatin: I was always fascinated by cities. When I studied urban planning at the Art Academy in Georgia, I started thinking about cities not on a level of planning individual buildings but on a larger scale. Afterward, I went to study in Barcelona, and that’s where I got acquainted with such topics as peripheral settlements and large housing estates, which I followed up in my PhD research, that is currently on pause. The research was connected with Gldani, one large housing estate in Tbilisi, which is considered to be a kind of micro-city in a city. Me and some friends decided to make a festival in that neighbourhood, and that’s how the whole Tbilisi Architecture Biennial started. Everything I do now started from this story.

Vivian: For me, I think it was somehow inevitable. I was trained as a musician and was always part of a community of musicians. At the same time, I always loved to observe public space, so when I had to make a choice about what to study, it was clear that I wanted to pursue urban planning. I was always curious to know how to integrate culture and communities, so I followed this as a master’s thesis about music in public space. What adds to this is the fact that I cannot choose only one thing. So I’m a tapas person, I’m doing tapas urbanism.

“Spatial Formations” by W2RKSHOP Collective

“Spatial Formations” by W2RKSHOP Collective

Background & Education

Katya: Here’s another question concerning the background and education. Sometimes I feel that you need to have formal education in the urban field. What’s your feeling about it?

Vivian: I am unsure if it’s a must. Maybe it’s just a neighbour who doesn’t have any education in urban studies or architecture, but who is a wonderful placemaker.

Tinatin: When I think of the “typical” background in a certain context, for example, Tbilisi, I feel that the people involved in this field are not architects or planners. They are rather active neighbours or environmental activists. Also, there are lawyers because they know what is allowed, and we need more of such people.

Vivian: Yeah, I think it’s quite similar in Greece. Placemakers used to come mostly from the activist level. As it started to professionalize, it is getting easier for people with a background in urban studies, architecture, or planning to find professional opportunities in city making, but we’re still in a very early stage in Greece. But, for instance, we have Jane Jacobs who was a journalist, and I think she was one of the greatest thinkers about city making. And psychologists as well, I think, can do great work when it comes to placemaking.

Katya: Could you share some strategies for growing in your field and finding opportunities to learn?

Vivian: After I finished my university degree, I did several trainings, mostly in the field of facilitation and hosting, this gave me the path to go where I wanted to go. I think the greatest teachings I have received was being part of communities who want to bring change.

Tinatin: What I have learned is through the experience of working with a lot of different people from various countries. I learned how to realize the ideas that people have, and this is my actual job. I think non-formal education is essential, especially in societies with an authoritarian regime, in post-socialist countries. This is how you can learn to think outside the box.

Topics & Projects

Katya: What are you working on right now and which topics do you consider most relevant for you at the moment?

Tinatin: Last year I started to research the physical space of the borders and shared borders. There it’s difficult to identify which country it belongs to, that’s why I call it a common territory. As part of the summer field school One Caucasus, we researched Marneuli Municipality in Georgia, bordering Armenia and ethnically settled mainly by Azerbaijanis. During one week we explored different villages and saw what common everyday practices people have there.

Katya: What were those common practices?

Tinatin: We had a focus on food and products – consumption, production, and distribution.

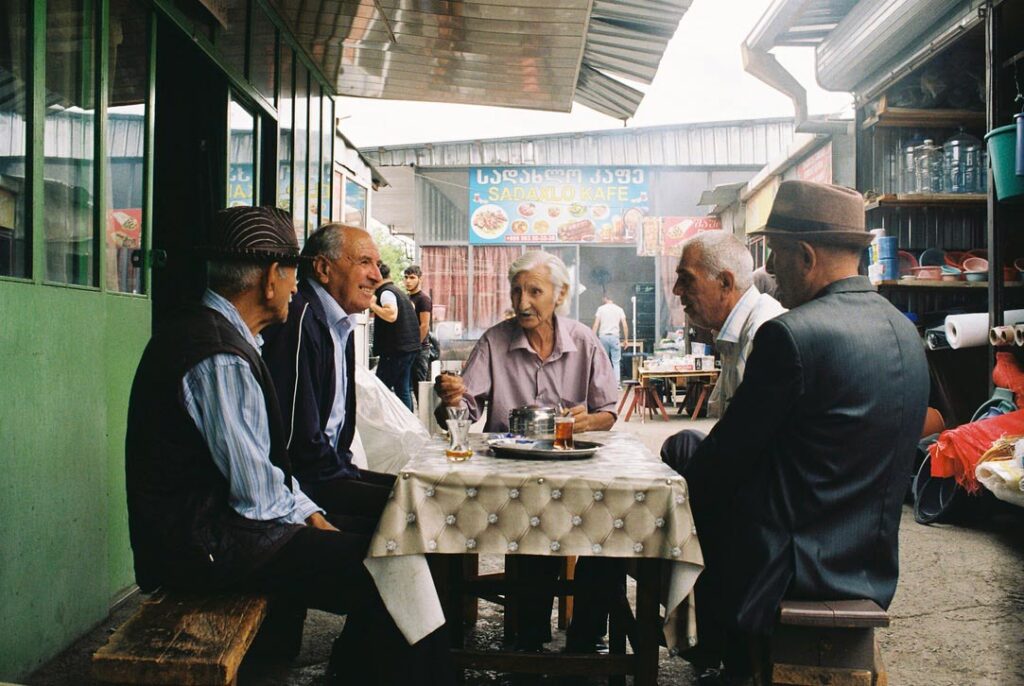

For example, we recorded local recipes and went to bazaars and tea houses. In the bazaar, one person from Armenia was selling food that someone from Azerbaijan was buying. Georgia becomes a common territory for them, they talk to each other, even though outside they have a conflict.

Vivian: Tinatin, the concept of a common territory sounds relevant in the Balkans as well. In my case, it’s very difficult to specify one topic. The drive to initiate a project comes from three needs of mine. First of all, it’s important to have a participation and community-building aspect in each project. Secondly, it also has to do with culture and education. And the third one is the systemic approach and politics of governance on different levels.

My favourite project is when I worked with students on a weekly basis. It was an educational programme on how they can start changing the school and the neighbourhood. Seven years after the project, I’m still hearing from them, what kind of impact it has had on them.

Katya: Is it more important for you to work on a local level or on a global level? How do you take a decision?

Vivian: I think the global level allows me to take perspective and connect the dots, while the local one allows me to be part of it. So I’m trying to have both in my daily practice.

Tinatin: I try to find and identify burning local topics and apply them globally, not the other way around. By now, it always worked: all three editions of Tbilisi Architecture Biennial were very international. In the last edition, we were talking about different aspects of temporality, asking, what’s next?

Katya: So what’s next?

Tinatin: I have no idea. In our region, what’s next is a difficult question.

Katya: I think you should stay very flexible in this field. And when we talk about work with the community, have you ever had any cases of negative feedback or situations where your approach didn’t work?

Tinatin: Last year, we had a positive experience during the TAB opening. We organized an exhibition in one building where the IDPs (internally displaced people) from Abkhazia lived. We had to be careful not to romanticise this situation. The connection happened because we worked together with some of the residents. During the opening, one guy started telling us bad things, but one of the residents asked him to leave, as he didn’t even live there.

In other cases, people tore our posters or stole exhibition objects. During the first edition, they even stole the entire installation and repurposed it to sell secondhand clothes. It was amazing.

Vivian: It is a sign of success, if you think about it, the people got engaged with the installation.

I had the following situation. During a participatory project with school students, we invited the local community to join us in placemaking workshops. The neighbours came down and started yelling at us. This was the first time I had experienced such hostility. The municipality’s lack of action on bigger problems made our small intervention feel like an annoyance to them.

Out of this, I came to two findings. The first one is that it’s quite important to learn how to negotiate. And the other one is to understand what is already there. Even though it was inside my neighbourhood, I didn’t know about that problem.

Public & Private

Katya: When we work in public spaces, we often build collaborations with private or public institutions. What is your experience with this?

Vivian: In the context of Greece, it is quite tricky. There’s more need to look for public or private funds, which leads to a discussion over where the red lines are, and where they might be crossed. Would you take money from a big corporation to do a small pocket park in your neighbourhood? Would you allow a big company to fund the project inside your school? For me, I do have my red lines, but I’m ready for negotiations if the impact behind the project is worth it, or if I receive the green light from the community.

Tinatin: For me, it’s not so complicated to answer this question. It’s impossible to realise something on a bigger scale using only local funds, so we always rely on funds like Creative Europe. Tbilisi City Hall helps us with small financial support and necessary permissions during the Biennial. It’s hard to cooperate with public institutions, especially with the Ministry of Culture, which is really authoritarian now, but we still do it, as it’s taxpayer money and we aim to benefit the city.

Vivian: In Athens, we’re now having a very political and systemic discussion with a public state. It’s not only selling public lands, but also offering the platform to private companies to create and manage public spaces. An example is the hill of Lycabettus in the centre of Athens. To my knowledge and understanding, the government didn’t have money to renovate it, so one private company agreed to pay for it. The problem here is not that someone will pay for the renovation, but under what conditions it’s going to be. Now they’re trying to gate a hill, which is ridiculous, and this is happening in many areas in Athens.

At the same time, when I was in Milan, I went to a new publicly-owned park in the neighbourhood of Isola designed and managed by a private foundation. It was a well-maintained place open to everyone. I didn’t have to consume to be there. There was some security, but it was discreet. So for me, it’s a matter of the system behind the management of this space. But of course, public land should still be public land.

Sustainable Work & Making a Living

Katya: Yet, another and last painful question about how to make a living as a city practitioner and if there are any ways to make it more sustainable.

Vivian: My business model, to be honest, is that I often work outside of Greece in order to be able to work inside Greece. I’m trying to invest at least 30-40% of my earnings in underpaid or voluntary work in Greece. Finding the balance is difficult because I need much more time for local projects. But it’s improving, and I’m happy to see that formal urban planning here is starting to open up to the approaches we bring to the table.

Tinatin: When I started working in this field, I only had debts, because we organised the festival without any resources. Now the hard work is slowly paying back. Currently, I can live with this, since other things are also coming up, but it’s not a job where you immediately start to earn well.

Katya: What do you wish for in the field of your work?

Vivian: I think we should think more about mental sustainability. Many of us, or at least the people I know, are overworked. Sometimes we cannot put a limit while working with communities and spaces, simultaneously trying to navigate bureaucracy, finances and systems. I don’t have a solution besides taking better care of ourselves and saying no.

Tinatin: I agree, I work so many hours I don’t even count them anymore. I’d like to answer this question from a different angle. What could bring more quality to our cities and neighbourhoods is the understanding of commonness. This square is ours, and we are responsible for it. We can go and make a demonstration there, sit there, or have a picnic. This understanding was completely gone in Georgia, and people often don’t care about anything beyond their own apartments. It’s slowly changing, and with my work, I’d like to inspire people to look behind their doorstep.

One more thing I wish for is to stay critical. Always. If the municipality gives me money for a project, it doesn’t mean I cannot criticise them, or I should be afraid of them.

Vivian: I liked it! I think our work is very political, be it cultural work, education, or field work. Sometimes we avoid seeing the politics behind it, but it is not helpful. We’re practising politics.